|

|

|

Presentation

of Squire Kevin Bryan

Conclave,

Brotherhood of Dragonslayers

26

February 2000

Few things in today's society evoke more controversy than our present system of Juvenile Justice, as practiced in the fifty one jurisdictions currently present in the United States. On any given day the news media presents numerous stories of juvenile offenders: ranging from status offenses to the horrors of a massacre such as Columbine High School. The hue and cry across the nation is for the government to do something about current levels of juvenile crime; especially those involving violence unprecedented in our national history.Each of the fifty one jurisdictions, is currently writing legislation to address the public's concern over youth violence and criminal activity. It should be noted, there is little if any cohesion between the jurisdictions and their interpretation of the public's desire to reduce or eliminate juvenile crime. We are faced with fifty one separate concepts of how to go about the business of dealing with Juvenile Offenders. While there is some universal legislation in force, compelling the jurisdictions to cooperate with each other in dispensing juvenile justice, the lack of a national policy on handling Juvenile Justice creates a system which substantially infringes on the Constitutional Rights of Juveniles, and creates a separate near secret judicial arrangement where juveniles are routinely denied due process equal to that required for adults charged with the same or nearly the same offenses.

There is little doubt, juveniles have a limited capacity to reason through the Constitutional issues involved in dispensing justice in respect to society's expectations. For most juveniles, contact with the Juvenile Justice system leaves them in doubt as to whether justice or retribution was the issue at hand. Courts routinely bypass "due process" in the interest of "public safety". In the 224 year history of this nation, only ten major Supreme Court decisions have directly effected Constitutional protections provided juveniles. The current system of Juvenile Justice is a national tragedy, inflicting itself on a segment of the population which has no voice in establishing criteria by which the system administers legislation or fulfills the mandate of society to reform juveniles who have gone outside the expected norm.

A brief study of Supreme Court decisions which directly addressed Juvenile Constitutional Rights, show the nation was not overly concerned about judicial decisions affecting juveniles until 1899 when Cook County, Illinois established a separate system to deal expressly with juveniles. Since that time, we have consistently debated whether or not Constitutional protections extend to juvenile offenders. There is no provision in the Constitution establishing an age requirement before the protections included therein are applicable to a citizen of the United States. The debate rages whether juveniles should be afforded different standards of justice, or simply be considered "little criminals" and face the same standards required of adults. The inherent problem is that juveniles do not have the same reasoning capacity as adults, ergo do not have the ability to distinguish the nuances in the laws, nor do they have the capacity to rationalize the effect of their actions.

Typically, juveniles are stripped of their Constitutional protections by a system designed to 'rehabilitate' a juvenile offender, rather than extract retribution or punishment. The sad fact remains, juveniles' Constitutional rights are routinely skirted by the very Courts charged with dispensing justice. The current rush to transfer juvenile adjudications to adult courts, is an obvious knee jerk reaction to a system which has failed, and flies in the face of Kent v. United States (383 U.S. 541, 86 S.Ct. 1045, 161 L.Ed. 84) in which the Supreme Court, (Justice Fortas) stated:

The Court, in deciding the transfer of Kent to the adult court system was invalid, dealt with four major problems with the procedure followed by the juvenile court: lack of hearing, lack of effective assistance of counsel, access to records, and lack of a statement of reasons for the transfer. Considering a transfer from juvenile to criminal court is critically important, it was determined the juvenile court had exclusive jurisdiction to consider this matter, and that it must be guided by the essentials of due process and fair play. A meaningful review of the proposed transfer must include a full investigation, not merely assumptions as the basis for transfer. In line with this, an attorney representing the child was considered vital, the Court stating the juvenile court judge had no justification for failing to rule on the attorney's motions. Further, attorney access to records of the child was essential, particularly since the Court referred to them in making its transfer decision."There is evidence, in fact, there may be grounds for concern, the child receives the worst of both worlds; that he gets neither the protections accorded to adults, nor the solicitous care and regenerative treatment postulated for children."It is imperative the rights of juveniles are adhered to as evidenced by the most sweeping Supreme Court decision addressing juvenile constitutional rights: in re Gault (387 U.S. 1, 87 S.Ct. 1428, 18 L.Ed. 527). The Court determined in three specific areas the juvenile court failed to provide the child with the essentials of due process and fair play required in the Kent case.

The first of these areas related to notice of charges. Despite the fact the juvenile court judge stated the parents knew what the charges were and that the parents attended two hearings without objection, the Supreme Court stated it was not sufficient for "due process." Notice must be given, in writing, sufficiently in advance of a hearing to permit the child and the parents to be prepared. The notice must state what the charges are, with sufficient particularity, to determine what is being charged and what conduct is alleged to have taken place.

The second of these areas related to the right to counsel. To the argument the parents and the probation officer could be relied upon to protect the child's interests, it was pointed out neither might have legal knowledge. It was also pointed out both the probation officer, who is required to be an officer of the court, and the parents, who might have their own defense, may not be able to represent the child and the child only. In any situation where a child's liberty might be affected by commitment to an institution, "due process" requires notification of the child's right to be represented by an attorney, either hired by him or appointed by the court.

Finally, it was determined there are certain other rights which are so basic to a fair hearing they should be extended to juvenile proceedings: the right to confront accusers, the right to avoid self-incrimination, and the right to cross-examine any witness who appears in a matter against a child.

While these rights are familiar in the adult criminal system, it wasn't until Gault, they were transposed to the juvenile system. The fear juvenile proceedings would be turned into mini-criminal trials has not come to pass by affording juveniles proper Constitutional protections. If anything the system has benefited from the requirement. Note the Gault case is limited to the adjudication hearing and some pre-adjudication procedures. It specifically states that none of the "due process" or "fundamental fairness" standards are made applicable to the disposition phase. The disposition phase remains subject to the doctrine of parens patriae and is to be applied subjectively, so that each child is dealt with individually.

Once the Supreme Court established "due process" in the juvenile system other issues presented themselves for resolution. The standard of proof established for adult courts is that of beyond a reasonable doubt unlike that required for juveniles of "preponderance of evidence". In criminal cases proof is required to be beyond a reasonable doubt, which means evidence taken as a whole tends to exclude every other reasonable explanation with moral certainty. In re Winship (397 U.S. 358, 90 S.Ct. 1068, 25 L.Ed.2d 368) arose from New York where the standard of proof in juvenile court was the same as that required in civil proceedings; mere preponderance of evidence. The case presented the question of which standard of proof should be required in juvenile court: whether, or not, proof beyond a reasonable doubt is among the essentials of due process and fair treatment required during the adjudicory stage when a juvenile is charged with an act which would constitute a crime if committed by an adult. The Court held "mere preponderance of evidence" was insufficient to sustain a finding which would deprive a child of liberty. The "beyond reasonable doubt" standard attached to juvenile proceedings, requiring the state to prove its case, through fact, rather than merely assuming.

Another major question arising, is the right of trial by jury. In McKeiver v. Pennsylvania (403 U.S. 528, 91 S.Ct. 1976, 79 L.Ed.2d 647) the Supreme Court held a trial by jury was inconsistent with the mandate of the Juvenile Justice system to protect the rights of the accused. The Court refused to impose all adult criminal rights since it was believed judges could determine the facts as well as a jury. The objection remains, as to whether a single judge can be impartial in determining the facts, noting historically decisions have favored the state. At present no juvenile right to a jury exists, however, in the interest of due process and standards of fairness, a child potentially faced with loss of liberty, should be afforded the protections of the Constitution and the judgment of an impartial jury.

With the current push toward moving juvenile cases into the adult system, we must visit two decisions regarding Double Jeopardy in that a juvenile adjudication is equated to a criminal conviction. In Breed v. Jones (421 U.S. 519, 95 S.Ct. 1779, 44 L.Ed.2d 346) a juvenile court held a hearing, adjudicated Jones delinquent. After adjudication but before disposition the juvenile court found him to be unamenable to treatment in the juvenile system. He was transferred to adult criminal court, where he was found guilty and sentenced to the penitentiary. The subsequent conviction was challenged as being double jeopardy.

Jeopardy denotes risk, typically associated with criminal prosecution. Double jeopardy has generally been defined as being put at risk of the same peril twice. The Supreme Court decided this case violated double jeopardy provisions of the Constitution when it pointed out that jeopardy attached when the juvenile court started hearing evidence on the delinquency petition. After that point, a criminal prosecution based on the same act would be double jeopardy. In addition, the Supreme Court concluded for the purposes of the fifth amendment prohibition against double jeopardy,"in terms of potential consequences, there is little to distinguish an adjudicatory hearing, such as was held in this case, from a traditional criminal proceeding". Consider how strongly the Court felt about this issue: the opinion was 9-0.

In deciding Swisher v. Brady (438 U.S. 204, 98 S.Ct. 2699, 57 L.Ed.2d 705) the Supreme Court addressed delinquency cases heard by masters in Maryland. Children whose cases were tried before masters, objected to the state procedure for providing de novo, or new, hearings before the juvenile court judge, or supplemental findings to those of the master by the juvenile court judge. The objections were solely on the grounds of double jeopardy, wherein the children held the hearing before the master constituted adjudication therefore precluded the state from re-trying the case before a juvenile judge. The Supreme Court, in this instance, declined to overturn the State. Perhaps because of the usefulness of masters and the increasing caseloads of judges, this procedure was found not to violate due process and fundamental fairness standards. The Supreme Court said: to the extent the juvenile court judge makes supplemental findings in a manner either sua sponte, in response to the State's exceptions, or in response to the juvenile's exceptions, and either on the record or in a record supplemented by evidence to which the parties raise no objection - he/she does so without violating the constraints of the Double Jeopardy Clause of the U.S. Constitution. The majority of juvenile courts across the country employ similar procedures for a master to hear certain cases in lieu of the juvenile judge, most generally those cases involving traffic, or status offenses. In the majority of cases, the findings of the master end the adjudication phase; then are merely reviewed by the juvenile judge and accepted prima facia. In cases where the judge has substantial questions as to relevance of fact, or admissibility of evidence, it is proper for the judge to re-try the case in the interest of fairness and due process. There is no objection to the judge conducting additional inquiry into the facts, provided the disposition of the case is not adjusted upward to impose additional punishment.

We are all familiar with the requirements of Miranda, most notably the requirement to advise a detainee of his/her right to an attorney prior to questioning. A twist was addressed in Fare v. Michael C. (442 U.S. 707, 99 S.Ct. 2560, 61 L.Ed.2d 197) in which the detainee requested his Probation Officer in lieu of an attorney. The question before the Court was whether the request for his probation officer was the same as asking for a lawyer, so that questioning could not continue.

In this specific case, Michael C. asked for his probation officer. The probation officer was not informed while the police continued questioning him. During questioning Michael incriminated himself and the 'confession' was later used in adjudication. While not specifically addressed by the Court, the question remains if Michael equated his Probation Officer with a qualified attorney in ability to provide substantial legal advice. In a 5-4 decision the Supreme Court ruled the request did not require the police to stop the interrogation. While the juvenile probation officer did hold a position of trust with the child being questioned, he was not in a position to offer effective legal advice like a lawyer. The dissenting opinions take the position that when a child being interrogated by the police asks for an adult who is obligated to protect his interests, he is invoking the protection promised in Miranda v. Arizona. It makes little sense to assume a 'trusted adult' would not make provisions adherent to Miranda, ergo the request for such "trusted adult" must invoke the protections promised in Miranda.

A particularly sticky issue facing juvenile justice is that of "preventive pre-trial detention". While there is certainly a need to protect the juvenile and the community at large, there is also the issue of fundamental fairness and due process. The Supreme Court addressed this issue in Schall v. Martin (467 U.S. 253, 104 S.Ct. 2403, 81 L.Ed2d 207). In brief, based on information provided by police, a family court judge remanded Martin to "preventive pre-trial detention" pending a fact finding hearing. While in detention, Martin instituted a habeas corpus class action on behalf of "those persons who are, or during the pendency of this action, will be preventively detained pursuant to the New York Family Court Act. The class action sought a declaratory judgment the statute violated the Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. On the basis of evidence presented, the district court rejected the equal protection challenge but upheld the due process claim. The New York Court of Appeals confirmed.

The statute in question in this case permitted a brief pre-trial detention based on a finding of a "serious risk" that an arrested juvenile may commit a crime before his return date. The Supreme Court addressed two issues:

1) Does preventive detention under the statute serve a legitimate State objective.

2) Are procedural safeguards contained in the statute adequate to authorize the pre-trial detention of at least some juveniles charged with crimes?As to the first issue, the Supreme Court decided society has a legitimate interest in protecting a juvenile from the consequences of his criminal activity.

As to the second issue, the Court stated "due process requires a pre-trial detainee not be punished". In other words, no action can be taken which can not be redressed.

This becomes a highly sensitive issue when "pre-trial detention" is used in a manner inconsistent with "due process". In many jurisdictions, juveniles are routinely remanded to custody based solely on information provided by the arresting officer. This detention can last from several hours, to several days, depending on the circumstances surrounding the case. Deprivation of liberty can not be redressed, after all you can't return time that has elapsed. Imposition of incarceration, no matter how benign, is still deprivation of liberty without the protections of due process provided in the U.S. Constitution.

The Court provided a statute was essentially Constitutional if it contained procedural safeguards:

1) there was no indication in the statute itself, preventive detention is used or intended as punishment;

2) the detention was strictly limited in time:

3) detained juveniles are entitled to an expedited (72 hours) fact-finding hearing; and

4) the conditions of confinement appeared to reflect the regulatory purposes relied upon by the State.Given the regulatory purpose for the detention, and the procedural protections that preceded its imposition, the Court concluded a statute permitting pre-trial detention for a juvenile is valid under the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

While appearing adequate prima facia, the Court stopped short of providing adequate protections to juveniles in "pre-trial" detention. Unfortunately, detained juveniles are routinely subjected to punishment while they are incarcerated pending adjudication hearings. Juvenile detention facilities are not designed to keep "pre-trial" and "adjudicated" juveniles separate, often subjecting the "pre-trial" detainee to the same treatment afforded juveniles serving time as determined by the court. The jurisdictions contend establishing separate facilities for pre-trial detainees would be cost prohibitive, ergo an unnecessary drain on public funds better spent toward rehabilitating juvenile offenders. In too many cases, the 'pre-trial' detention is the only punishment meted out to a juvenile when the State fails to prove its case, or provide adequate probable cause to continue prosecution of the accused. In some jurisdictions, pre-trial detention is a matter of course, involving neither judge nor competent authority in review of the facts surrounding the need for incarceration. Police routinely confine juveniles in facilities with adult offenders, in clear violation of the prohibitions against such incarceration.

The last two cases presented here address the imposition of capital punishment (death penalty) on juveniles. Both cases invoked the "cruel and unusual punishment" prohibition in the Constitution wherein the Court was asked to rule on an age limit in determining the imposition of the death penalty on a juvenile. In Thompson v. Oklahoma (101 L.Ed.2d 702, 108 S.Ct. 2687) it was shown Thompson, age 15, along with three older persons, actively participated in a brutal murder. After a hearing, the court concluded "there are virtually no reasonable prospects for rehabilitation of subject within the juvenile system and that he should be held accountable for his acts as if he were an adult and should be certified to stand trial as an adult." In the penalty phase of the trial, the prosecutor asked the jury to find two aggravating circumstances: "that the murder was especially heinous, atrocious, or cruel; and that there was a probability the defendant would commit criminal acts of violence that would constitute a continuing threat to society." The jury found for the first condition, but stopped short of the second, and fixed Thompson's punishment at death. The U.S. Supreme Court agreed to consider whether the execution of the death sentence would violate the constitutional prohibition against the infliction of "cruel and unusual punishments" because Thompson was only 15 years old at the time of his offense.

The Court decided that contemporary standards of decency confirmed their judgment, such a young person is not capable of acting with a degree of culpability justifying the death penalty. The Court found complete or near unanimity among all fifty one jurisdictions in treating persons under age 16 as minors for several important purposes: voting, serving on a jury, driving without parental consent and marrying without parental consent. The Court found it most relevant that all states have enacted legislation extending juvenile court jurisdiction to no less than the 16th birthday. Of the 18 states who have expressly established a minimum age in their death penalty statutes, the Court found all of them require the defendant have attained at least the age of 16 at the time of the capital offense.

The second factor the Court examined in determining the acceptability of capital punishment to the American public is the behavior of juries. The Court found in the prior four decades, in which thousands of juries had tried murder cases, the imposition of the death penalty on a 15-year-old offender was abhorrent to the conscience of the community.

In deciding whether it would be "cruel and unusual" to execute Thompson, in particular, the Court came to several conclusions. The reasons why juveniles are not trusted with the privileges and responsibilities of an adult also explain why their irresponsible conduct is not as morally reprehensible as that of an adult. The Death penalty is said to serve two principal social purposes: retribution and deterrence of capital crimes by prospective offenders. The Court decided neither of these purposes would be fulfilled by executing a 15-year-old. Given the lesser culpability of the juvenile offender, the teenager's capacity for growth and society's fiduciary obligations to its children, retribution is simply inapplicable to the execution of a 15-year-old offender. As for the deterrence rationale, the likelihood the teenage offender has made the kind of cost-benefit analysis that attaches any weight to the possibility of execution is so remote as to be nonexistent.

The Court was asked to "draw a line" that would prohibit the execution of any person who was under the age of 18 at the time of the offense, and refused to do it. It did, however, conclude the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments prohibit the execution of a person who was under 16 years of age at the time of his/her offense.

The issue was revisited in Stanford v. Kentucky (106 L.Ed.2d 306, 109 S.Ct. 2969) when the Court rendered a decision in consideration of two consolidated cases. Stanford aged 17 years 4 months, and Wilkins aged 16 years 6 months, at the time of their offenses. The U.S. Supreme Court discerned neither a historical nor a modern societal consensus forbidding the imposition of capital punishment on any person who murders at 16 or 17 years of age. They concluded such punishment does not offend the Eighth Amendment's prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment. Therefore, it affirmed the judgments of the State Supreme Courts. A concurring opinion concluded the death sentences should not be set aside because it is sufficiently clear no national consensus forbids imposing capital punishment on 16-17-year-old murderers.

Four Justices joined in a dissent, stating they believed to take the life of a person as punishment for a crime committed when below the age of 18 is cruel and unusual - thus prohibited by the Eighth Amendment. The dissent concluded the death penalty for those under 18 makes no measurable contribution to the acceptable goals of deterrence nor retribution, essentially for the same reasons given in Thompson v. Oklahoma.

Currently, we are faced with myriad questions revolving around juvenile rights. Historically, the Supreme Court has stopped short of providing all the Constitutional protections afforded citizens provided those 'citizens' have not attained their majority. Under the present system of Juvenile Justice, children's rights are consistently skirted under the guise of protecting the "best interest" of the child. Juvenile courts are still cloaked from public view in a misguided belief the secrecy of proceedings will not taint a juvenile in later life. In reality, the cloak gives juvenile courts unlimited power to infringe upon the child's rights, denying due processes demanded under the Constitution.

While it is not the stated intention of legislators to establish a "mini-criminal" system of juvenile justice; reality shows the movement toward stiffer penalties, lower ages at which a case is transferred to adult courts, and a demand for greater latitude in dealing with juvenile offenders clearly precludes establishing a system consistent with providing additional Constitutional protections to juvenile offenders. Under the present system of juvenile justice, what few Constitutional protections are provided fall well short of that required to protect the 'best interest' of the child. As a nation we should demand from our legislators a system of juvenile justice which affords not the worst of both worlds, but the best of both worlds. Constitutional protections must be afforded all citizens, regardless of age. The founding fathers recognized the inherent problems of a government which failed to adhere to fundamental fairness in dispensing justice, specifically attaching to our Constitution a Bill of Rights limiting that government from infringing upon the basic freedoms granted by the Constitution.

Since its inception in 1899, the juvenile justice system has consistently avoided public view of its machinations. Under the guise of providing children a system designed to rehabilitate rather than punish, juvenile courts have become kangaroo courts in which a child is afforded few protections and fewer opportunities for rehabilitation. The current trend toward stiffer penalties clearly shows the intent of the juvenile system to extract punishment rather than provide rehabilitation to those children unfortunate enough to fall within its purview. Contrary to media hype, only a small minority of children comprise the bulk of cases currently before the justice system. These same children are those least able to defend themselves from the excesses of the courts, therefore need not fewer protections but greater protections coupled with a public review of every case. Only through dragging the juvenile justice system into the light of day, will we be able to properly construct the kind of rehabilitation necessary to change the behavior of errant children in regard to society.

Juvenile prisons in the United States are a national disgrace, a blot on the idealism envisioned by our founding fathers where in free men could enjoy the fruits of their labors and follow the dictates of their hearts. A juvenile justice system which not only allows, but encourages, retribution against its constituents should not be allowed to continue unharnessed. It behooves each of us to take a long critical look at a system gone completely out of control. It is time for us, concerned citizens and victims of the system alike, to stand together in dismantling the self-serving machinations of those specifically charged with protecting the best interest of children. We must take the cloak off, expose those who would under the mantle of justice deny a portion of our society the protections guarantied by the Constitution.

The time has come for this nation to reassess, and redesign, the juvenile justice system. We have struggled long and hard to prove this nation, conceived in liberty and dedicated to the principal all men are created equal, shall not perish from the face of the earth. We must establish a juvenile justice system that not only protects society, but provides for the rehabilitation of those juveniles who have transgressed. We must establish a system of juvenile justice consistent with the vision of our founding fathers, that government shall not abridge the rights of the governed. It is past time for us to demand from our legislators, laws consistent with rehabilitative and educational needs of children, rather than headline grabbing exhortations against youth violence and rising crime. It is our responsibility to take control of a juvenile justice system that has digressed into an inquisition; rather than the vision of providing those of tender years that which is necessary for them to become productive members of our society.

Each and all of us assembled here, have experienced first hand the machinations of our present juvenile justice system. It is our voices which must be heard. It is our experiences, and the experiences of everyone who has come in contact with the system, which must be presented to society at large. We can not continue to tacitly condone the insidious erosion of juvenile constitutional protections. We must as a body present a united front, bred in brotherhood, demanding the juvenile justice system in this country protect not only the rights of children, but enter into the twenty first century in providing rehabilitation to those who fall under the courts purview. It is time for us to reassess the system which has in the words of Justice Fortas provided "grounds for concern the child receives the worst of both worlds: that he gets neither the protections accorded adults, nor the solicitous care and regenerative treatment postulated for children."

Welcome

Here Be Dragons

Hear Ye, Hear Ye

Special Boys

Life With Mikey

In My Best Interest

The Beat Goes On

On Using Protection

Breaking the Cycle of Abuse

Seeing With New Eyes

Adoption Option

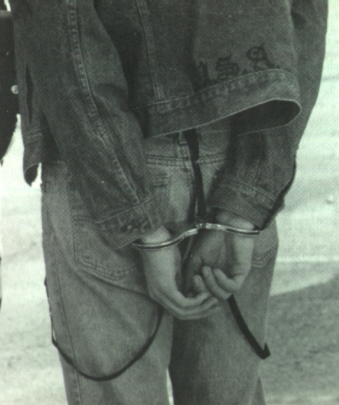

Juvenile Constitutional Rights

Male Survivors of Sexual Abuse